Art and Social Justice: An Interview With Veronica Alvarez

A self proclaimed ‘nerd,’ Veronica Alvarez’ resume and list of accomplishments is strongly aligned with her passion for education and social justice. She is currently the Executive Director of Community Arts at CalArts, has worked with elementary, high school, and college students, teaching subjects including Spanish and Ancient Mediterranean history. She also worked at the Getty Museum for over 16 years and has served as an education consultant for UCLA’s Fowler Museum and Chicano Studies Research Center, and the State Department of Cultural Affairs in Chiapas, Mexico.

I admire how she has integrated Latin studies with art, for example, at LACMA she teaches an Art and Social Justice course that uses artworks in the museum's collection to encourage critical thinking about historical and contemporary social justice issues to inspire real-world connections and elevate student agency. I wanted to learn more about her story growing up as a Latina in the US, her career path, what inspired her to pursue this field-specifically regarding her Art and Social Justice course, and finally, what has been her most rewarding endeavor.

After taking her Art and Social Justice course at LACMA, I was inspired. I too am passionate about the far-reaching impact of art, especially when utilized for social justice and education. I knew that if I was able to connect with her and she was willing to participate, she would be an ideal candidate for my oral history report. To my surprise and delight, I was able to connect with her through CalArts and she was kind enough to agree to speak with me.

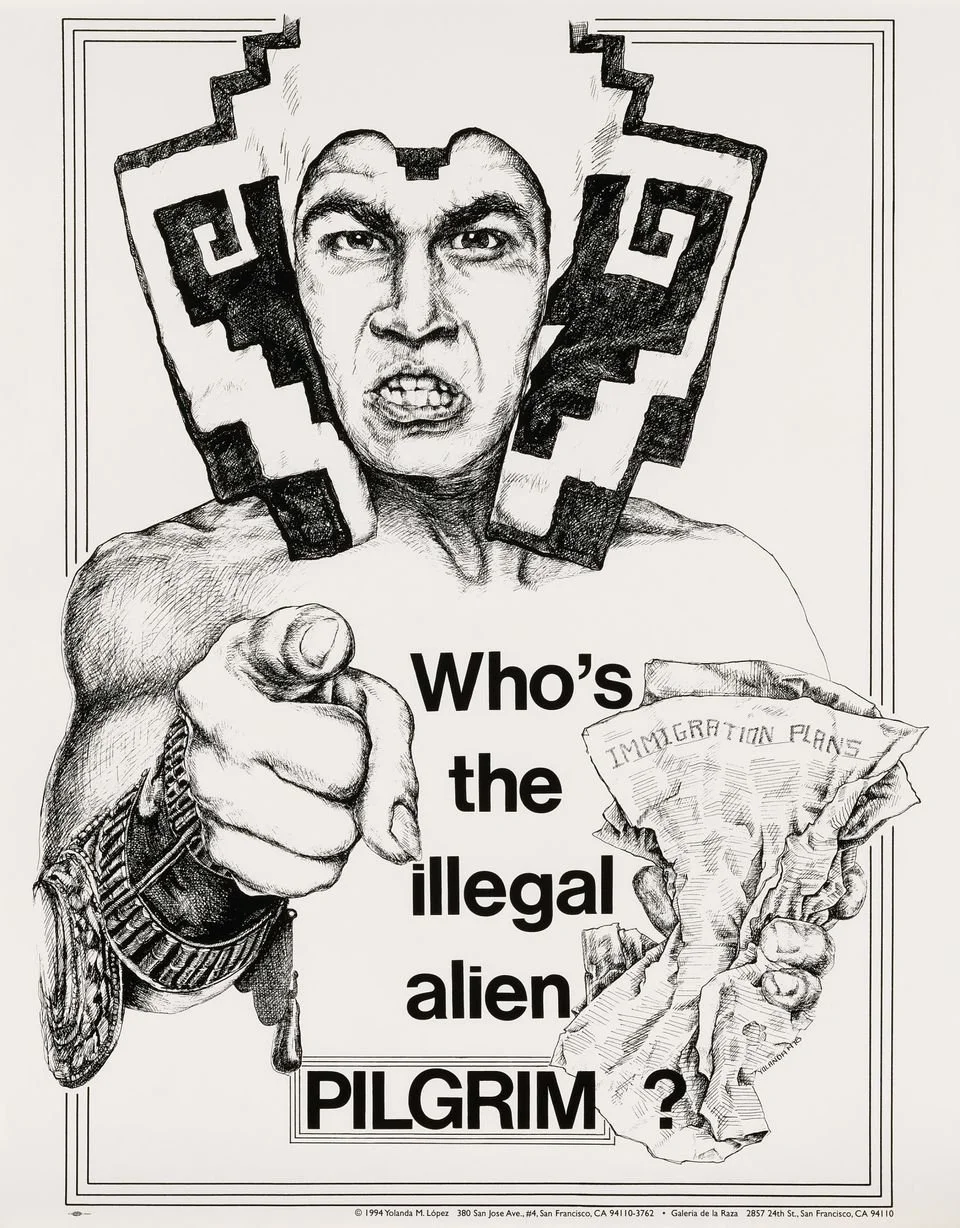

Prior to our meeting, I had told her how much I enjoyed her Art and Social justice course, specifically her lecture on Yolanda Lopez. Within the lecture, Alvarez shares a lithograph Lopez made in 1978 called, Who’s the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim? It was created for a campaign about immigrant rights organized by the Committee on Chicano Rights in San Diego, in response to President Jimmy Carter’s plan to build a fence along the southern border of the United States and divide immigrant communities by granting different types of amnesty. It was used again during the Trump administration.

As you can see in this image, the figure looks angry. He has his teeth clenched, his eyebrows are furrowed, and he’s pointing directly at the viewer. Yolanda López took this image based on the “I Want You” Uncle Sam poster. She uses the image along with the text, and the figure is dressed in an indigenous headdress, either suggesting Mayan or Aztec [heritage]. He has these very interesting indigenous elements along his forearm. By putting him in this indigenous headdress, he’s really challenging the viewer and pointing directly at us, “Who is the illegal alien, pilgrim?”

This reminded me of learning about Manifest Destiny and the Mexican-American War, but also of watching Harvest of Empire. I was heartbroken to learn that after the Great Depression, it was possible that up to sixty percent of those deported to Mexico were US citizens. "The Mexicans function as a reserve labor force in good times in America, and an expendable force in the bad times." The lack of care for so many immigrants as they are shipped in and out of the US at the will of the government and its economy is deplorable.

This quote in particular stands out from the film when I view Lopez’ lithograph. "As an illegal alien, to call someone illegal is the beginning of dehumanizing."

When Veronica and I finally met, I told her that I believe that time is the greatest gift you can give someone and how much I valued hers, so I got straight to the questions! Originally from Michoacán, born in the town where cotija cheese is made! (She was delighted to share!) A tiny town that can be walked through in 20 minutes. She moved to the US with her family when she was 9. “I was undocumented,” she tells me. She grew up in San Fernando valley- one of 9 kids- she is number 7. She was the last one born in Mexico, 2 younger siblings born in the US.

I asked Veronica how she felt arriving in a new country with different cultures and how she handled the transition. She started by sharing that she grew up during the time that Pete Wilson was the governor of California. He was a Republican who was essentially anti-immigration and didn’t believe in providing education for immigrants. She mentioned Prop 187, which Isidro Ortiz elaborates on in a YouTube video, ‘The Impact Of Prop 187, 20 Years Later.’ Fortunately Prop 187 never passed but it did politicize the Latin community and California has become a safe Democratic state largely because of this. Veronica endured a lot of ‘go back to your country’ and ‘speak english!’ In addition to other anti-immigrant sentiment. She recalls that she was ashamed to speak spanish. She even took Spanish in high school to keep up the facade that she was not familiar/fluent. I mention her lecture where she mentions that Yolanda Lopez is ashamed that she speaks Spanish. She is pleasantly surprised that I retained that from the course and agrees with the parallel.

Veronica shares that with the challenges she experienced growing up, she threw herself into her studies and had 24 credits before she even started college! Her favorite of all her high school courses was AP art history and that is where her passion for art began. She continued to university, attending Cal State Northridge, featuring one of the first and biggest Chicano studies departments.

“Chicano Studies opened the door to possibilities of employment on university faculties,” said Raul Ruiz, professor emeritus in the Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies at Cal State Northridge, which hired him in 1970. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Cal State LA in 1967, and went on to earn his master’s and Ph.D. at Harvard.” From ‘The Birth of Chicano Studies’ by Sandy Banks.

Veronica shares a similar experience to Ruiz, “When I attended CSUN, that’s really when I stepped into my own. I learned that being Latina was something to be proud of! I began to see being bilingual as an asset.” She appreciated the educational system and took advantage of what the state of California provided.

I asked Veronica if there were other artists I should look into as advocates of social justice, she immediately mentioned her friend, Barbara Carrasco and her mural, L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective, which contains 51 scenes that illustrate the marginalized groups in Los Angeles as a timeline that starts with indigenous people through history to the Zoot Suit riots. I shared with her that I learned about Carrasco’s mural in the very beginning of my class and look at this beautiful mural every day on Canvas!

She tells me that Carrasco’s husband, Harry Gamboa Jr. teaches at CalArts and she sees him all the time. His work as a member of the pioneering Chicano art group, Asco (Spanish for nausea), was resistant and political. Over the years, art collectors, museum curators and academics have hailed Asco and Gamboa for presenting the realities of a community that was long ignored and provocatively translating the universality of its experiences.

“I guess growing up in L.A. in the early 1950s amid the efforts to dehumanize and demonize the Chicano population made me want to find effective ways to explode those stereotypes. We were creating art that explored the various elements of the human experience in such a way that helped people recognize that what was happening in the Chicano community was universal.” (CSUN Prof Harry Gamboa’s Work to Be Exhibited in England and Mexico. Carmen Ramos Chandler. CSUN Today.)

Gamboa’s photo from the Asco protest at LACMA because they didn’t feature any Latin artists.

I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity to learn so much from Veronica Alvarez. I can see that she holds education in the highest regard partly as a result of the opportunity almost being taken from her in her youth with Prop 187. I thank her again as our interview comes to a close. My final question is to ask her what her most rewarding endeavor is and she tells me that being the Executive Director of Community Arts at CalArts provides her with the opportunity to share and integrate art education to places throughout California where people lack this valuable resource. She shares that student participation as well as graduation rates increase dramatically when art education is provided to students. I agree with her that this is certainly an achievement to be proud of and we both agree that art is absolutely more than just something to look at. Art can encourage students to do better, it can express anger, it can inform people of social injustices, and it can be the catalyst for change.