The Birth of Venus

When you first view the canvas, you are initially struck by the ivory female figure that

appears to be carved from marble. Her soft, tranquil gaze welcomes you to the same place of

peace she is in. Her lush, golden hair spirals in the wind whilst she is balancing, or perhaps

floating, upon a massive shell. It is upon viewing the shell that my mind begins to question the

meaning behind it. Within this analysis, I would like to uncover the motivation for the creation of

the painting by Sandro Botticelli named, The Birth of Venus. This work was completed in 1486,

taking about two years to finish. Created with tempera on canvas, it is approximately five feet

seven inches high and nine feet wide.

With relation to the size of this work, the subject is essentially a full-size nude. She is

modestly covering her statuesque physique as a female to her left, the nymph, Pomona, greets

her with a regal, rose-colored gown adorned with delicate flowers and gold embroidered edges.

An interesting point made by Dr. Beth Harris in the Smarthistory video, is the difference in

Venus’ modesty versus Eve’s expressed shame in Masaccio’s Expulsion of Adam and Eve From

Eden (1425), considering their mannerisms are almost identical.

At the time this painting was produced, nudes were not common. Only in religious contexts

were they accepted, but not for beauty as in the Greco-Roman era. Botticelli’s choice to paint

Venus nude makes this painting a key catalyst at the beginning of the Renaissance. This painting

was commissioned by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco di’Medici. The Medici family funded and

encouraged the intellectual and cultural growth that became known as the Renaissance.

A unique trait of this work is that it is on canvas. At this time, most artists were painting on

wood, and the use of canvas was rather uncommon. It appears to give more texture to the

painting, which I noticed when I zoomed in.

There seems to be no mistake that Venus’ body truly looks like a statue. Botticelli referenced

classical statues to create the subject’s near-perfect physique. Upon closer examination, you will

notice that her left arm is longer than her right. Additionally, her neck is more swan-like than

human, giving her a more elegant and regal grace.

As she lightly poses upon the shell, my initial impression of this representation is a metaphor

for a pearl; smooth, flawless, illuminating beauty. Upon further investigation,

artdependence.com states a shell may represent ‘love and fertility,’2 which would be accurate

since Venus is in fact the god of love and fertility. There is also a reference to the ‘womb,’

plausible as this is the moment of her birth (gods can be born as adults).

To Venus’ right, Zephyr and Chlorus are blowing her toward the shore. These two stunning

creatures are entangled in a loving embrace, their side of the painting is showered in roses. I

think the initial response would be that the roses are reaffirming Venus’ delicate femininity,

however, I see that they are truly surrounding Zephyr and Chloris. The flowers emphasize their

love for each other as well as foreshadow Chloris’ future. Within their story in mythology, they

marry, and Zephyr turns Chloris into a deity, Flora- the goddess of Spring. This is displayed in

Botticelli’s sister painting, Primavera, Cloris is transformed into Flora before our eyes.

Saint Sebastian: Guido Reni vs El Greco

It all begins with an idea.

I've focused on the theme of Saint Sebastian, choosing two paintings with this subject: Reni’s "St Sebastian" (1619), and El Greco's "St Sebastian" (1610-1614). During this period, Saint Sebastian was a prevalent theme among artists. The narrative involves his torture, depicting him tied to a tree and subjected to repeated arrow shots due to his unwavering faith. Within this storyline, artists found a compelling avenue to explore the depiction of the male nude form.

In Reni's depiction of St. Sebastian, the saint's skin is portrayed as exceptionally smooth in texture, color almost a translucent alabaster. A single puncture wound, located just below his rib, is depicted with minimal blood. Sebastian is surrounded by a subtle and almost imperceptible halo as he gazes towards the heavens. Notably, there is a pronounced use of a bright coral hue on his ears, cheeks, nose, and lips, complementing the prevalent blue undertone throughout his form. This warm coral tone is skillfully incorporated into various highlights across his physique.

Apart from Sebastian and the linen draped around his hips, the overall tonal value of the painting is quite dark. Although there is a hint of light on the horizon line, the space surrounding Sebastian remains in shadow. This darkness creates a dramatic contrast with the pale figure of Sebastian bound to the tree. In the lower right corner, three uniformed figures are visible, with one seemingly giving instructions. In the upper right corner, a solitary cloud balances the composition alongside the illumination on the horizon. Sebastian's body dominates the left side of the canvas, with his knee seemingly pointing towards the uniformed figures in the bottom right and the arrow aligning in the same direction. However, Sebastian's gaze is directed upward, towards the heavens.

The color palette of the composition is predominantly cool, with warm tones reserved for the skin highlights and the uniformed soldiers. This deliberate use of warm tones guides the viewer's attention to these focal points. While the overall painting is aesthetically pleasing, I don’t appreciate the coral tones on Sebastian's skin, they appear somewhat jarring. This effect may be influenced by the computer screen, potentially distorting the true colors and giving the impression of an enhanced, almost Technicolor-like quality.

El Greco's portrayal of St. Sebastian is distinctly unique. The initial observation that stands out is the undulating rhythm of the saint's figure. Sebastian's limbs and torso are elongated, and even his neck exhibits notable length. This rhythmic flow guides the viewer's eye across the canvas, seamlessly complementing the surrounding scene of trees and mountains, which also possess their own rhythmic grace. There is a pronounced contrast between the arrows and the rest of the painting; everything else exhibits a more organic, curvilinear appearance, with the arrows acting almost as punctuation marks with their rigidity.

El Greco employs space in an intriguing manner. While the lower portion of the canvas creates depth through perspective and fading hills, the upper portion appears somewhat more two-dimensional. The predominant color palette is a range of cool tones, with St. Sebastian's skin depicted as a pale white with hints of cool-toned red and a subtle gray-blue undertone. The painting itself has undergone alteration, with the legs being severed from the original, which features the landscape in the background. It’s suggested that the landscape reflects the location of the commissioner's intended scene behind St. Sebastian, seeking his blessing for the territory, however it is said that Sebastian had never visited the area.

The values in the painting are broad, featuring bright white highlights on Sebastian's skin in stark contrast to the dark tree to which he is tied. His figure seems outlined with a darker color, emphasizing both his form and the overall curvilinear aesthetic. Texture is evident throughout the canvas, notably in the background with trees, leaves, rocks, and mountains. The linen wrapped around Sebastian's waist exhibits a tactile quality, adding to the overall impasto style of the painting. Despite the loose, painterly brushstrokes, there is a softness in the depiction of Sebastian's skin.

The scale of Sebastian in relation to the canvas is notably large, providing him with a heightened sense of importance and intensity. The composition strategically directs all focus onto the main subject, St. Sebastian. Personally, I found this rendition particularly engaging. The curvilinear rendering of the form and the rhythmic flow of lines create a captivating visual journey up and down the canvas, adding to the overall appeal of El Greco's unique interpretation of St. Sebastian.

Virgil Ortiz

It all begins with an idea.

I learned so much attending the Virgil Ortiz presentation. I find him to be such an inspiration not only because of his integration of many medium, but because in spite of his success, he is incredibly humble and down to earth.

I was initially in Professor Holmes Museum Curation course before I had to drop it to switch to life drawing on MW. In her course, we were preparing to welcome Virgil to Saddleback and curate a show featuring his work. One of the videos I watched as I researched his story, he says that he shares his process because ‘It is not our secret to keep.’ That comment had such an impact on me and made me reflect on how many artists are very secretive about their processes.

Making pottery is a part of his tribal and familial lineage. He learned from his mother when he was young and realized he could make money to buy Star Wars gear with the money he made from his own pottery. At around 16 years, he began to do his own thing and explore his own style. When the gallery buyer, ‘Uncle Bob,’ would come to purchase the family’s work, he noticed Virgil’s pieces and invited him to come see the warehouse and studio. No one in the family had ever been invited before, and when he went, he saw all these other pieces made by his ancestors that looked exactly like the work he created when he was inspired to explore his own style! He said he knew at that moment that the Pottery Mother was beckoning him and he never looked back. (amazing!)

Virgil’s raison d’etre is to spread knowledge and the truth about the Pueblo Revolt as America’s first revolution and to uncover the whitewashed story spun by the government. He has traveled globally with this message and his stunning work, one collection purchased in its entirety by Cartier!

This was an incredibly educational and highly motivational talk. I am so grateful I was able to attend and even more grateful that Saddleback has the privilege to host him as a resident artist.

Art and Social Justice: An Interview With Veronica Alvarez

It all begins with an idea.

A self proclaimed ‘nerd,’ Veronica Alvarez’ resume and list of accomplishments is strongly aligned with her passion for education and social justice. She is currently the Executive Director of Community Arts at CalArts, has worked with elementary, high school, and college students, teaching subjects including Spanish and Ancient Mediterranean history. She also worked at the Getty Museum for over 16 years and has served as an education consultant for UCLA’s Fowler Museum and Chicano Studies Research Center, and the State Department of Cultural Affairs in Chiapas, Mexico.

I admire how she has integrated Latin studies with art, for example, at LACMA she teaches an Art and Social Justice course that uses artworks in the museum's collection to encourage critical thinking about historical and contemporary social justice issues to inspire real-world connections and elevate student agency. I wanted to learn more about her story growing up as a Latina in the US, her career path, what inspired her to pursue this field-specifically regarding her Art and Social Justice course, and finally, what has been her most rewarding endeavor.

After taking her Art and Social Justice course at LACMA, I was inspired. I too am passionate about the far-reaching impact of art, especially when utilized for social justice and education. I knew that if I was able to connect with her and she was willing to participate, she would be an ideal candidate for my oral history report. To my surprise and delight, I was able to connect with her through CalArts and she was kind enough to agree to speak with me.

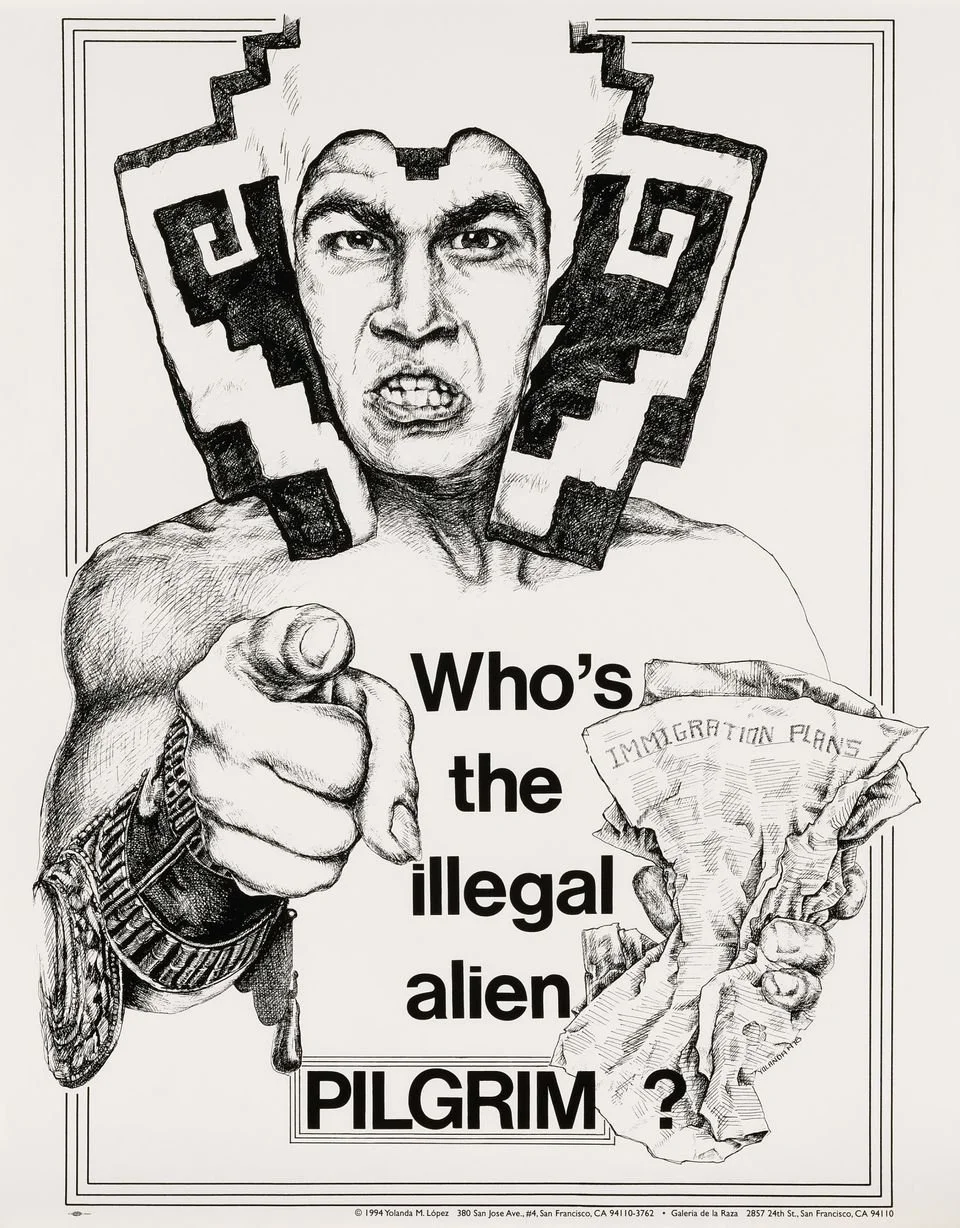

Prior to our meeting, I had told her how much I enjoyed her Art and Social justice course, specifically her lecture on Yolanda Lopez. Within the lecture, Alvarez shares a lithograph Lopez made in 1978 called, Who’s the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim? It was created for a campaign about immigrant rights organized by the Committee on Chicano Rights in San Diego, in response to President Jimmy Carter’s plan to build a fence along the southern border of the United States and divide immigrant communities by granting different types of amnesty. It was used again during the Trump administration.

As you can see in this image, the figure looks angry. He has his teeth clenched, his eyebrows are furrowed, and he’s pointing directly at the viewer. Yolanda López took this image based on the “I Want You” Uncle Sam poster. She uses the image along with the text, and the figure is dressed in an indigenous headdress, either suggesting Mayan or Aztec [heritage]. He has these very interesting indigenous elements along his forearm. By putting him in this indigenous headdress, he’s really challenging the viewer and pointing directly at us, “Who is the illegal alien, pilgrim?”

This reminded me of learning about Manifest Destiny and the Mexican-American War, but also of watching Harvest of Empire. I was heartbroken to learn that after the Great Depression, it was possible that up to sixty percent of those deported to Mexico were US citizens. "The Mexicans function as a reserve labor force in good times in America, and an expendable force in the bad times." The lack of care for so many immigrants as they are shipped in and out of the US at the will of the government and its economy is deplorable.

This quote in particular stands out from the film when I view Lopez’ lithograph. "As an illegal alien, to call someone illegal is the beginning of dehumanizing."

When Veronica and I finally met, I told her that I believe that time is the greatest gift you can give someone and how much I valued hers, so I got straight to the questions! Originally from Michoacán, born in the town where cotija cheese is made! (She was delighted to share!) A tiny town that can be walked through in 20 minutes. She moved to the US with her family when she was 9. “I was undocumented,” she tells me. She grew up in San Fernando valley- one of 9 kids- she is number 7. She was the last one born in Mexico, 2 younger siblings born in the US.

I asked Veronica how she felt arriving in a new country with different cultures and how she handled the transition. She started by sharing that she grew up during the time that Pete Wilson was the governor of California. He was a Republican who was essentially anti-immigration and didn’t believe in providing education for immigrants. She mentioned Prop 187, which Isidro Ortiz elaborates on in a YouTube video, ‘The Impact Of Prop 187, 20 Years Later.’ Fortunately Prop 187 never passed but it did politicize the Latin community and California has become a safe Democratic state largely because of this. Veronica endured a lot of ‘go back to your country’ and ‘speak english!’ In addition to other anti-immigrant sentiment. She recalls that she was ashamed to speak spanish. She even took Spanish in high school to keep up the facade that she was not familiar/fluent. I mention her lecture where she mentions that Yolanda Lopez is ashamed that she speaks Spanish. She is pleasantly surprised that I retained that from the course and agrees with the parallel.

Veronica shares that with the challenges she experienced growing up, she threw herself into her studies and had 24 credits before she even started college! Her favorite of all her high school courses was AP art history and that is where her passion for art began. She continued to university, attending Cal State Northridge, featuring one of the first and biggest Chicano studies departments.

“Chicano Studies opened the door to possibilities of employment on university faculties,” said Raul Ruiz, professor emeritus in the Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies at Cal State Northridge, which hired him in 1970. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Cal State LA in 1967, and went on to earn his master’s and Ph.D. at Harvard.” From ‘The Birth of Chicano Studies’ by Sandy Banks.

Veronica shares a similar experience to Ruiz, “When I attended CSUN, that’s really when I stepped into my own. I learned that being Latina was something to be proud of! I began to see being bilingual as an asset.” She appreciated the educational system and took advantage of what the state of California provided.

I asked Veronica if there were other artists I should look into as advocates of social justice, she immediately mentioned her friend, Barbara Carrasco and her mural, L.A. History: A Mexican Perspective, which contains 51 scenes that illustrate the marginalized groups in Los Angeles as a timeline that starts with indigenous people through history to the Zoot Suit riots. I shared with her that I learned about Carrasco’s mural in the very beginning of my class and look at this beautiful mural every day on Canvas!

She tells me that Carrasco’s husband, Harry Gamboa Jr. teaches at CalArts and she sees him all the time. His work as a member of the pioneering Chicano art group, Asco (Spanish for nausea), was resistant and political. Over the years, art collectors, museum curators and academics have hailed Asco and Gamboa for presenting the realities of a community that was long ignored and provocatively translating the universality of its experiences.

“I guess growing up in L.A. in the early 1950s amid the efforts to dehumanize and demonize the Chicano population made me want to find effective ways to explode those stereotypes. We were creating art that explored the various elements of the human experience in such a way that helped people recognize that what was happening in the Chicano community was universal.” (CSUN Prof Harry Gamboa’s Work to Be Exhibited in England and Mexico. Carmen Ramos Chandler. CSUN Today.)

Gamboa’s photo from the Asco protest at LACMA because they didn’t feature any Latin artists.

I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity to learn so much from Veronica Alvarez. I can see that she holds education in the highest regard partly as a result of the opportunity almost being taken from her in her youth with Prop 187. I thank her again as our interview comes to a close. My final question is to ask her what her most rewarding endeavor is and she tells me that being the Executive Director of Community Arts at CalArts provides her with the opportunity to share and integrate art education to places throughout California where people lack this valuable resource. She shares that student participation as well as graduation rates increase dramatically when art education is provided to students. I agree with her that this is certainly an achievement to be proud of and we both agree that art is absolutely more than just something to look at. Art can encourage students to do better, it can express anger, it can inform people of social injustices, and it can be the catalyst for change.

Bonaventura Berlinghieri: Exploring the Byzantine Artist's Altarpiece Dedicated to the Life of Francis of Assisi Through the Elements of Design

It all begins with an idea.

The era of Byzantine art encompasses a unique style of artistic expression characterized by elaborate gold leaf, elongated human forms, and a unified focus of spirituality. Bonaventura Berlinghieri is an artist whose works left an indelible mark on the art world. In particular, his altarpiece dedicated to the life of Francis of Assisi stands as a testament to his mastery of the Late Byzantine style, showcasing his ability to capture both the physical narrative and spiritual essence of his subject. This masterpiece demonstrates Berlinghieri's artistic skill while integrating various principles of design to create a visually captivating and spiritually evocative composition.

The altarpiece, created in 1235, is a large panel painting crafted with vibrant tempera and gold leaf on wood. Measuring approximately six feet in height, the work consists of several individual scenes arranged in a narrative format. Each scene depicts a significant spiritual moment from the life of Saint Francis, demonstrating the artist's deep understanding of the saint's transformative journey and his ability to communicate these events to the viewer. Berlinghieri's meticulous attention to detail and his skillful execution of Byzantine aesthetics are evident in each panel or ‘apron scene,’ resulting in a cohesive and harmonious composition.

Contrast plays a crucial role in Berlinghieri's altarpiece. The contrast between light and dark areas creates a dramatic effect, emphasizing the significance of each scene. The use of chiaroscuro demonstrates clear tonal contrasts which are often used to suggest the volume and modeling of the subjects depicted. The dark intensity of Saint Francis’ robe and the dramatic contour of his face juxtaposed with the vibrant gold leaf background heighten the visual impact of the artwork, drawing the viewer's attention to this large central figure holding the most visual weight. The presence of gold leaf enhances the panel's ethereal quality, implying the saint's connection to the divine.

Emphasis is utilized in Berlinghieri's altarpiece to highlight the central figure of Saint Francis. He is portrayed larger than the surrounding figures, ensuring that the viewer's attention is drawn towards him, displaying a visual hierarchy. Additionally, the use of contrast to emphasize the stigmata on Saint Francis’ hands and feet further enhances his spiritual significance within the composition.

Balance is achieved through the symmetrical arrangement of the panels. The central panel featuring Saint Francis serves as the focal point, flanked by angels even with his shoulders and three smaller panels on each side. This symmetrical balance evokes a sense of stability and harmony, reflecting the divine serenity associated with the saint.

The anatomical proportions are characteristic of the Byzantine style featuring elongated human forms. Upon close observation, the limbs appear to be rendered particularly long in this painting. Within each apron scene the buildings look rather disproportionate to the size of the characters, which makes them appear to be about eight feet tall.

Repetition and rhythm are achieved through the consistent use of certain visual elements throughout the altarpiece. The regular repetition of each scene’s frame and irregular repetition of the buildings contained within creates a sense of unity and continuity. The rhythmic flow of the composition guides the viewer's eye from one panel to the next, effectively narrating the story of Saint Francis' life.

Patterns are integrated in the altarpiece to enhance its visual appeal and create a sense of texture. Berlinghieri uses intricate patterns and decorative motifs in the backgrounds and architectural elements, adding visual interest to the composition.

Movement is intended to be conveyed through the gestures and poses of the figures. The drapery of the characters within the frames suggest more of a sense of movement in comparison to the robe Saint Francis wears in the center, which appears static and heavy, showing no movement at all.

Variety is skillfully incorporated into the altarpiece through the depiction of different scenes from Saint Francis' life. Each panel presents an important moment within his life, ranging from his humble beginnings of preaching to the birds to the miracle of receiving the stigmata. His narrative is an example for the parishioners to strive to live a holy life as he did. Even the three knots in his belt are viewed as a reminder to live a life led by the three traits of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

Finally, unity is achieved through the cohesive integration of all the design principles mentioned above. Despite the diverse scenes and elements within the altarpiece, Berlinghieri skillfully harmonizes them to create a unified whole. The consistent style, color palette, and compositional structure contribute to the overall unity of the artwork.

This altarpiece not only showcases Berlinghieri’s technical skill but also reflects the spiritual and religious climate of the time. It exemplifies the strong influence of Franciscan spirituality, emphasizing poverty, humility, and devotion to God. This piece served as a focal point for religious devotion, inviting viewers to contemplate the life and teachings of Saint Francis and seek spiritual guidance through their encounter with the artwork.

In conclusion, Bonaventura Berlinghieri's altarpiece dedicated to the life of Francis of Assisi is a demonstration of his artistic mastery and his utilization of the principles of design. Through the skillful use of contrast, emphasis, hierarchy, balance, proportion, repetition, rhythm, pattern, movement, variety, and unity, Berlinghieri creates a visually captivating and spiritually evocative composition that continues to inspire and awe viewers nearly a millennium later.